During my five years in Chengdu I knew Ran Yunfei as a scholarly bon vivant who combined brilliant, erudite conversation with a wonderful zest for life. An iconoclastic writer and social critic appreciated even within the Chinese Communist Party for his writings on improving Chinese education, he is a Chinese patriot intensely concerned with better Chinese society although he steered clear of politics and any explicit criticism of the Communist Party. Ran, originally from Chongqing, graduated from the Chinese Literature Department of Sichuan University and was friendly with some other Chengdu writers such as Liao Yiwu, Yu Jie and Wang Yi. Despite avoiding criticism of the Communist Party, Ran Yunfei was detained for two months when the Communist Party panicked in the aftermath of the so-called Jasmine Revolution in 2011. After his release from formal detention he was kept under strict house arrest for several months and his travel even within China was restricted for several years. Since he has published several books on Chengdu local history.

The Ran Yunfei article translated below fascinated me on several levels:

- First, to get a better understanding of Chinese and foreign research on Chengdu where I lived for five years — the byways I ran down doing this translation and some of the online sources it led me to, especially the resources on the University of Toronto website abut Canadian missionareis in Chengdu.

- Second, to better understand the state and possibilities of Chinese research on history these days when some historians are accused by Party hacks of historical nihilism if research leads where the Party prefers not to go.

- Third, is local history less sensitive? Or is it the focus on secondary issues ostensibly not so important that allows for more freedom? Ran Yunfei’s title to his review of some recent work on Chengdu history is revealing: “How to Turn Secondary Topics into First-rate Scholarship”

- And how is local history changing as new sources are discovered and news approaches inspired by the social sciences change our understanding of the past. Could some of this work be in part a gentle push back by Chinese historians at the Chinese Communist Party’s anti-foreign, anti-missionary narratives?

Background

Ran Yunfei Wikipedia article

- 2008: Ran Yunfei: “Where Will the Fear End? A Talk that Could Not Be Delivered”

- 2010 Ran Yunfei: Pathological Stability is the Root of Social Instability

- 2010: Ran Yunfei on Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Peace Prize

- 2010: Ran Yunfei — “How I Lived My Life in the Year 2010”

- 2011: Wang Yi’s Diary — Now I Must See My Friend Ran Yunfei Become a Prisoner

- 2011: China Releases Dissident Blogger, With Conditions

- 2012: Ian Johnson’s New York Review of Books interview with Ran Yunfei: Learning How to Argue

- 2015: A Writer Turns to Christ

Books by Ran Yunfei

“What I Think About Zhuangzi”

“Incurable Disease: Crisis and Critique of Chinese Education”

“The Exile of Handwritten Manuscripts”

“The Road to a Foolish Empire”

“The Vanguard Trapped in a Snare: Borges”

“The Sharp Autumn: Rilke”

“Living Like Tang Poetry”

“Entering Chengdu from the Sideline of History”

“The Reasons Why I Got Addicted to Zhuangzi”

“Wu Yu and the Republican Era He Lived In”

“The Lungs of Ancient Shu: the Chronicle of Daci Temple”

“Give Freedom to the One You Love” (collection of published essays on Chinese education)

Ran Yunfei | How to Turn Secondary Topics into First-rate Scholarship

August 12, 2019 15:21 (Read: 257)

Reprinted from WeChat public account: Everyone, August 12, 2019

On the Research Center of Local Archives website

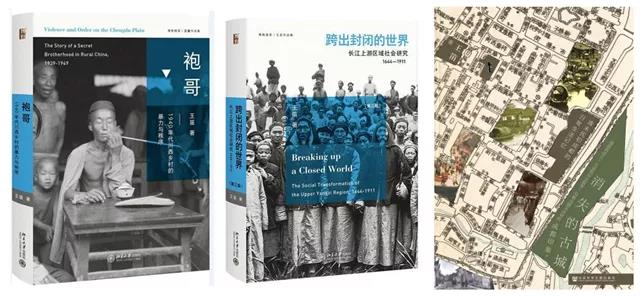

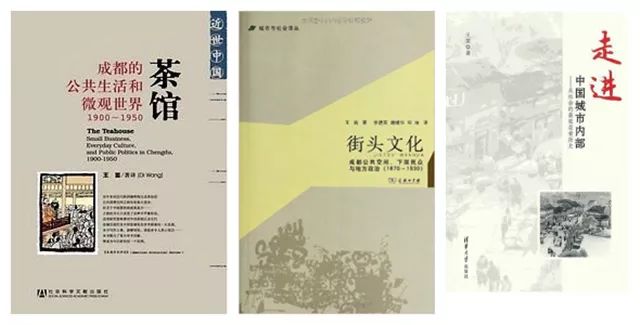

I spent a month reading reading all six Chinese language books published by historian Wang Di 王笛 thus far. They are:

- 《跨出封闭的世界:长江上游区域社会研究(1644—1911)》(Third Edition, Peking University Press, September 2018,[“Breaking Out of a Closed World: A Study of the Upper Yangtze River Region Society (1644-1911)”] abbreviated as “Breaking Out”),

- “Street Culture: Chengdu’s Public Space, Lower-Class People, and Local Politics (1870-1930)” 《街头文化:成都公共空间、下层民众与地方政治(1870—1930)》(2013 edition, Commercial Press, abbreviated as “Street Culture”),

- The Teahouse: Small Business, Everyday Culture, and Public Politics in Chengdu, 1900-1950《街头文化:成都公共空间、下层民众与地方政治(1870—1930)》(2010 edition, Social Sciences Academic Press, abbreviated as “Teahouses”),

- 《走进中国城市内部:从社会的最底层看历史》(2013 edition, Tsinghua University Press, [Entering Inside Chinese Cities: A Historical Perspective from the Bottom of Society”] [abbreviated as “Entering”),

- Violence and Order on the Chengdu Plain: The Story of a Secret Brotherhood in Rural China, 1939-1949 《袍哥:1940年代川西乡村的暴力与秩序》(2018 edition, Peking University Press, abbreviated as “Violence and Order”), and

- 《消失的古城:清末民初成都的日常生活记忆》(2019 edition, Social Sciences Academic Press, [“The Vanished Old City: Memories of Daily Life in Late Qing and Early Republican Chengdu” ] abbreviated as “Vanished”).

I agree and disagree with Wang Di on some issues. In the spirit of seeking truth, I will share them with fellow enthusiasts.

[Translator’s Note: Three of University of Macao Professor Wang Di’s books are available in English:

- Violence and Order on the Chengdu Plain: The Story of a Secret Brotherhood in Rural China, 1939-1949

- The Teahouse: Small Business, Everyday Culture, and Public Politics in Chengdu, 1900-1950 and

- Street Culture in Chengdu: Public Space, Urban Commoners, and Local Politics, 1870-1930, End note.]

Wang Di’s six books can be roughly categorized into four types:

First, there are theoretical explorations combined with his research experience. These books aim to enlighten future scholars, showcase his work to colleagues, and disclose it to readers, such as “Entering.“ It can be said that by reading this book, one can easily understand Wang Di’s other research. However, he does not engage in the study of the history of historiography or historical philosophical thinking; instead, he interprets the methods he has employed in his own research.

Second, his earliest monograph, “Breaking Out,” as the title suggests, represents the first step in academic research. It is through “Entering” that one can delve deeper. This book predominantly adopts a macro, national, long-term, and elite perspective, covering various aspects of the upper Yangtze River region’s society. It significantly differs from later micro-level studies, local perspectives, lower-class perspectives, and those focusing solely on certain aspects of Chengdu.

Third, “Street Culture,” “Teahouses,” and “Violence and Order” are the three books that constitute the core of Wang Di’s research and are well-known among the academic community or readers.

Finally, there is a non-academic popular work, “Vanished.” 《消失的古城:清末民初成都的日常生活记忆》 The notable feature of this book is that it transforms interesting and story-like footnotes into the main text.

The three books, Street Culture included, set Wang Di’s work apart from most previous Chengdu studies. Just as Sichuan cuisine offers many ways to cook a chicken and several ways to prepare chili, Wang Di’s expertise shines through in his varied research approaches. Of course, it takes a skilled chef to avoid monotony, as too much of the same is tiring. In the case of Chengdu, Wang Di’s is undeniably exceptional.

These days we don’t have a clear view of Chengdu’s history. Or rather, most of the so-called studies are nothing more than copying and recopying old stories, a mere excuse for professional employment and a waste of a life. Most of the research on Chengdu history, whether general history or individual studies, is highly traditional; few outside of the circle of professional historians know about it. It is the writing and research of non-historians, such as Li Jieren, Liu Shahe, Yuan Tingdong, Dai Jun, and others about Chengdu history that is well-known to the public.

Few books on the historical research of Chengdu can transcend the confines of academic circles as do the work of the professional historian Wang Di. This is because Wang Di’s writing does not stick to rigid academic language and concepts. Instead, he either tells stories or outlines historical details. Without compromising academic rigor, Wang Di’s writing aims to engage with his readers and win their interest much like the historical writings of authors such as Jonathan Spence and Philip A. Kuhn.

Of course, this does not mean that scholars’ previous research on Chengdu has been insignificant. Works like American scholar Kristin Stapleton‘s

- Civilizing Chengdu: Chinese Urban Reform, 1895–1937. Harvard East Asian Monographs, no. 186. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2000. Chinese edition published in April 2020 by Sichuan Wenyi Chubanshe under the following title: 新政之后:警察、军阀与⽂明进程中的成都 (1895-1937) and

- Fact in Fiction: 1920s China and Ba Jin’s Family. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016. Chinese edition published in June 2019 by Sichuan Wenyi Chubanshe under the following title: 巴⾦《家》中的历史:20世纪20年代的成都社会

provide different research perspectives from Wang Di, but they undeniably bring about a fresh understanding of Chengdu.

Other works such as

- Wang Dongjie‘s 《国家与学术的地方互动:四川大学国立化进程(1925—1939)》[“Interaction between the Nation and Academia: The Nationalization Process of Sichuan University (1925-1939)” ] and《国中的“异乡”:近代四川的文化、社会与地方认同》[ “The ‘Foreign Land’ in the Nation: Modern Sichuan’s Culture, Society, and Local Identity,” ]

- Li Deying‘s 《国家法令与民间习惯:民国时期成都平原租佃制度新探》[“State Laws and Folk Customs: A New Exploration of the Chengdu Plain’s Tenancy System in the Republican Era,” ]

- Liu Xinjie‘s 《民法典如何实现:民国新繁县司法实践中的权利与习惯》[ “How the Civil Code is Implemented: Rights and Customs in the Judicial Practice of Xin Fan County in the Republican Era,”]

as well as certain articles in the “Modern and Contemporary History” section of the journal 《川大史学》 [“Sichuan University Historical Studies”] journal, have greatly contributed to deepening our knowledge of Chengdu.

I recently read Qiu Shuo‘s”邱硕《成都形象:表述与变迁》[ “Chengdu’s Image: Representation and Transformation,] which can help us get a better understanding of the history of Chengdu’s image. However, if we examine the tension between anthropological “local knowledge” and national narratives as explained by Clifford Geertz, as well as the central and peripheral aspects of power distribution in political anthropology, we find we still need a more rigorous academic exploration.

Some may ask, why spend so much effort on reading these books?

First, although I am not originally from Chengdu, I have lived here for over thirty years, so I am interested in understanding everything that happens here. Second, I consider myself a Chengdu researcher, but I believe that compared to Wang Di’s research on Chengdu, I fall short. His methods, perspectives, and depth of research far exceed those of many others, including myself, — naturally this is related to his academic training. Although he is engaged in historical studies, he actually employs methods from other disciplines to approach his historical research. This means that he does not follow the traditional path of cultural and historical studies. This seemingly narrows Wang Di’s research down to special topics such as social aspects of the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, the Pao brothers, Chengdu teahouses, Chengdu street culture. Wang Di, however, is not a traditional scholar specializing in documenting the past of a particular locality. Wang Di combines microscopic history with a broad vision, as they say, “seeing the big picture through small details.”

On the other hand, his research approach is also part of the transformation in traditional historical research — a shift from holistic studies to an interest in minute details, from the pursuit of certainty to the description of uncertainty. Much like transition from the first to the third generation of the Annales School: seemingly minor yett profoundly meaningful. In brief, why has traditional historical research increasingly come to rely upon social science disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, economics, and religious studies? History by itself clearly lacks adequate explanatory power when confronting globalization and complex social issues. Of course, this problem is not specific to historical studies. This paradigm or trend has arisen from the cross-disciplinary nature of many fields, indicating the apparent limitations of many individual disciplines in isolation. If previous Chengdu research had some flaws in terms of being overly general or focused on trivial matters, then Wang Di’s writing reveals the texture of Chengdu’s social life through the combination of micro-histories with a broad vision. Wang Di’s practice resembles what the “middle-range theory” of the American sociologist Robert Merton preached, a reconciliation of a just-the-facts positivist rejection of theorizing and grand narratives lacking granular detail.

New Methods in Chengdu Research

Wang Di discussed research methods and historical materials about Chengdu in his book prefaces especially in “Approaching” (《走进》). Often he does not respond explicitly to criticisms from other scholars. These include Ma Min’s critique of Wang Di’s “Street Culture: Chengdu’s Public Space, Lower-class People, and Local Politics, 1870-1930” (published in the book 追寻已逝的街头记忆——王笛<街头文化:成都公共空间、下层民众与地方政治,1870—1930>评述》[“Modern Chinese Cities and Popular Culture” edited by Jiang Jin and Li Deying, pp. 359-391, New Star Press, 2008)] and Li Jinzheng’s 李金铮《小历史与大历史的对话:王笛<茶馆>之方法论》(《近代史研究》2015年第三期) “A Dialogue between Small History and Big History: Wang Di’s Methodology in ‘Teahouse” (published in the “Journal of Modern History Research,” 3/2015). Those two scholars made comparative and in-depth analyses of the two books “Street Culture” and “Teahouse.” Here apart from necessary references for the sake of discussion, references are kept brief. My approach to the discussion is twofold: comparing it with existing research on Chengdu and addressing aspects that have been rarely discussed by others or only addressed indirectly. Here I offer my own insights in order to provide a fresh perspective.

Major Topics and Real Issues

If you have read Wang Di’s books carefully, such as any of his works like “Teahouse” or “Approaching,” you can see that in the prefaces, he always explains and interprets his research methods and purposes, even defending them to some extent. Why does he do so? It is because his research methods in new cultural history and microhistory have not yet gained a complete consensus among his peers and readers in China.

Firstly, there are differences in readers’ understanding and expectations. For example, readers of “Violence and Order” (《袍哥》) may simply consider it as an interesting story. When it comes to tea culture, readers expect a good story, but the author’s considerations are founded on his understanding of grassroots legal decentralization and the power struggle between the authorities and the people.

Furthermore, rather than saying there are differences in the understanding of methods, materials, and purposes among fellow historians, it is more accurate to say that traditional Chinese historiography has a strong inclination towards grand narratives and ideological dynamics. The traditional approach of the “Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government” (《资治通鉴》) of a history aimed at serving practical purposes has significant market appeal and deeply ingrained psychology. To the extent that the authoritative 《近代史研究》2012年第四期 “Journal of Modern History Research” dedicated a column in its 4/2012 issue to discuss “中国近代史研究中的‘碎片化’””Fragmentation in Chinese Modern History Research,” and Wang Di responded with his article entitled 《不必担忧“碎片化”》”No Need to Worry about ‘Fragmentation.'”

Wang Di’s classic response to his peers is presented in a famous manner that hides the names of the critics, known as the “second-rate topic” “二等题目. It is not quite fair to call this a response because the proponent of the “second-rate topic” was not specifically criticizing his own research; others had already raised this argument. Given the reputation of the person who raised this question within the Chinese research community, Wang Di believed it was necessary to pre-emptively defend himself.

In his books “Teahouse” (p.14) and “Approaching” (p.16), Wang Di almost verbatim mentions this issue: “A highly respected and accomplished Chinese-American historian once advised, ‘Never work on second-rate topics.‘ Implicit in his words is the idea that only by choosing important subjects can one become an outstanding historian. Thus, he focused on major topics concerning the nation and people’s livelihood. His perspective resonated with many domestic historians. However, I have doubts about whether there truly exist so-called ‘first-rate topics‘ or ‘second-rate topics.'”

Wang Di does not mention by name the renowned Chinese-American historian he criticizes, who is known for his outspokenness and intellectual self-assurance. This historian is none other than Ping-ti Ho. Influenced by Zeng Guofan’s principle of “building a solid fortress and fighting deadly battles,” He Bingdi believed that in life, as well as in academic pursuits, one should address significant issues and focus on first-rate topics. This view was not his original creation but was said to him by the scientist Chia-Chiao Lin, whom he admired, during a conversation: “No matter what field you’re in, never work on second-rate topics.“《读史阅史六十年》p.104,广西师大出版社2005年版) [“Sixty Years of Reading and Studying History,” p.104, Guangxi Normal University Press, 2005 edition]. The nature of science makes the timeliness, urgency, difficulty, and cutting-edge nature of scientific research the central focus in selecting topics.

The essence of scientific research is solving problems (not necessarily practical, as in the case of famous conjectures in mathematics, to the point that mathematician G. H. Hardy believed the greatest function of mathematics lies in its uselessness), the concept of a “first-rate topic” appears inherently important. However, whether the emphasis on “first-rate topics” in scientific research can naturally be applied to research in the humanities and social sciences is uncertain, as the differences in their confirmability and falsifiability are evident. As for Ping-ti Ho , even extending this idea to a “Tsinghua University spirit,” seems to narrow the scope of group (the alma mater) spirit.

Wang Di’s criticism of Ping-ti Ho’s “first-rate topics” is not an attempt to deliberately sing a different tune just to be contrary. Rather, it reflects a shift in historical paradigms. The shift from positivist history in the West to the exploration of language and narrative, as well as new cultural and microhistorical approaches, occurred decades ago. In China, however, the dominance of grand narratives and utilitarianism continues to shape the mainstream of historical research. This is why Wang Di argues that there are not too many small-scale studies or so-called “fragments” but rather, that there are not enough of them.

Moreover, many historical studies today remain confined to traditional realms of literature and history and do not incorporate relevant social science methods. This is particularly true for most Chengdu studies. In other words, some historians are overly concerned about the encroachment of disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, and economics on the territory of history, blurring the boundaries of the field. Wang Di believes this unreasonable. Scholars who study the history of historiography should have the most say in this matter because they investigate the historical development of historical scholarship. Wang Di’s friend, Q. Edward Wang (Wang Qingjia 王晴佳) , who has made significant contributions to the study of the history of historiography, also supports Wang Di’s views, especially in《新史学讲演录》[“Lectures on New Historiography”].

In Wang Di’s view, those who focus on so-called “first-rate topics” may inevitably use them as a means to satisfy their ambition and desire to master the study of history. This is a characteristic of traditional Chinese intellectuals, who consider themselves elite and often adopt the mindset of advisers eager to offer advice at any time. This attitude compromises the relative independence of scholarly pursuits and lacks the attitude that truth should be sought for its own sake. .

Furthermore, while Ping-ti Ho employs some modern methods in his historical research, his historical perspective is still influenced by the Chinese tendency to treat history as a religion and the tradition of governance and practicality. As a result, Chinese historians had an almost instinctive influence of the official histories of the early dynasty and kingdom including of the Yin, Zhou, Jin and Chu and the Spring and Autumn Annals of Lu. The deep-rooted reverence of the Chinese for power also played a role. With power concentrated in political elites, particularly in the upper echelons, who control the allocation of resources. Therefore, it is not surprising that the imperial annals and official gazettes have always been the prime materials for Chinese history. The choice of research topics inherently carries power since it is connected to the worship of authority, something many Chinese historians feel passionately about. While the saying “Acquire literary and martial skills, and get in good with the imperial family” may sound harsh, many practitioners of history still operate on this principle.

Of course, this cannot be solely blamed on today’s Chinese researchers because this has been so for thousands of years. Even if now they live elsewhere, they are inevitably influenced by these things. Most humanities research is incomplete and uncertain and so is often influenced by preconceived historical perspectives. No one approaches the study of history without preconceptions. Total objectivity and value neutrality are merely ideals that cannot be fully achieved. Even in scientific research where it is difficult to completely escape preconceptions. Ultimately, historical perspectives are also influenced by worldviews and values.

Wang Di disagrees with He Bingdi’s views and repeatedly quotes a passage from Fernand Braudel in some of his books to signal his intention: “Unfortunately, our knowledge of those grand palaces exceeds that of the fish market. Fresh fish is transported to the market in water tanks, where we can also see a large number of dogs, wild chickens, and quails, and where we can make new discoveries every day.“ (Street Culture, p. 23)

Wang Di stresses: “Studying the everyday and studying the lower strata of society ultimately comes down to the problem of historical perspectives and methodology. Although our mainstream ideology constantly emphasizes that ‘the people are the driving force behind historical change,’ our historical research actually undervalues this driving force.” (Entering, p. 15) Plastic flowers serve a decorative purpose, and it is pointless to try to study their fragrance. However, the sentence “Do we not believe that our daily lives, compared to sudden outbreaks of political events 突发的政治事件 , are tied more closely to our destiny?” (p. 14) is worth deep consideration. Furthermore, in Wang Di’s view, focusing on the small scale to understand the bigger picture is practical: “Studying the most basic units of society and delving into the inner workings of cities will not hinder historians from examining more macroscopic and significant events; on the contrary, it will help them gain a deeper understanding of such issues.“ (Teahouse, p. 424)

What is a real question? Apart from the grand questions like “What is human nature?” or “Where do we come from and where are we going?. Aren’t there these questions wrapped up in the details of everyday life? “I believe that the importance of the research subject itself doesn’t exist; the key lies in whether the researcher has a macroscopic perspective. This requires historians to seriously consider how to handle those intricate details, just like building a house. The structure of the house is akin to the purpose and core of the book, while the bricks and tiles represent the details of the book. If there are only details, the building cannot stand.” (《走进中国城市内部:从社会的最底层看历史》(2013 edition, Tsinghua University Press, [Entering Inside Chinese Cities: A Historical Perspective from the Bottom of Society”] [abbreviated as “Entering”, p. 69)

Following this line of thought, a natural conclusion is reached: “The research value of history is not determined by the importance of the research subject itself, but by the historical perspective and interpretation of the research. Historians can discover profound connotations of understanding and comprehending history from seemingly ordinary objects. Historians have different understandings of what constitutes research value, often determined by their historical perspectives and methodologies.” (Entering, p. 71) I believe this is a powerful response to scholars who consider research topics more important than historical perspectives and methodologies.

Although Wang Di insists on microhistory, he does not lack a macroscopic perspective. From a sub-level perspective, he observes the city where he once lived. To what extent does he adhere to such methodology and historical perspectives? Just by reading the preface of the revised edition of his first book, “Breaking Out,” one can find out. He acknowledges being influenced by the G.W. Skinner’s core-periphery standard market area model and Fernand Braudel‘s total history. For example, he no longer sees popular beliefs as superstitions but changes them to traditional society with ideological implications. Wang self-critically acknowledges that the book is influenced by the elite perspective of cultural hegemony and discourse hegemony. Subsequent writings are all corrections in this regard.

This also represents a reaction against his earlier education under Wei Yingtao’s discourse research model. If you cannot dynamically view the academic development of a person, it may even be difficult to recognize from the titles alone that they are the works of the same person. For example, Sichuan University’s Chen Yingtao 隗赢涛 and Wang Di’s 《西方宗教势力在长江上游地区的拓展》(《历史研究》1991年第三期)”The Expansion of Western Religious Forces in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River” (Historical Research, 3/199)]. In fact, the statistical methods and quantitative research used in this article are perfectly aligned with the book “Breaking Out,” and much of the content is also included in Chapter 10,“传统文化的危机与现代意识的兴起” [ “The Crisis of Traditional Culture and the Rise of Modern Consciousness”]. By the way, Tang Yi, a master’s student guided by Chen Yingtao, 唐毅《近代四川教案的反思——从区域性教案看近代中西关系》[“Reflections on Modern Sichuan Missionary Cases: Examining Sino-Western Relations from Regional Missionary Cases”] (I have a copy of the annotated version of this paper), shares that same historical perspective. This is not only a common problem in most modern history research but also the result of students conforming to their teachers’ perspectives.

- Historiography and Local Anthropology

Prominent scholar Wang Qingjia, who has made significant contributions to the study of the historiography of history, states that the emergence of new cultural history is actually the result of the combination of historiography and anthropology 《新史学讲演录》[Lectures on New Historiography], p. 55, published by Renmin University of China Press, 2010). This helps us understand why Wang Di entered the field of new cultural history and microhistory and why he feels so comfortable in it. Let us not forget that his first book was deeply influenced by G. William Skinner, and G. William Skinner’s anthropological background enabled Wang Di to observe not only historical geography and administrative divisions but also the honeycomb structure of rural markets and the macroscopic division of urban areas. Wang Di’s academic training under William T. Rowe led him to deviate from the traditional historiography training in China and instead pursue studies in sociology, anthropology, and political science. This resulted in significant differences in his views on how history should be written, for whom, and what problems it should address.

Despite significant differences in research methods before and after his study abroad, it is worth discussing why Wang Di continues to research Chengdu. This aspect is the main cause of misunderstandings among readers and colleagues. China has a longstanding academic research tradition of focusing on the place where people live and having a sense of attachment to that place. Various perspectives, such as field surveys and practical application, lead scholars to delve into this field. Simultaneously, from the perspective of a scholar actively participating in local life and studying various aspects of the local society, particularly as an outsider utilizing local materials and familiarizing oneself with the living environment, combining research with life becomes a way to acquire identity and recognition.

In other words, scholars of this kind not only bring warmth and practicality to their research but also overcome the dichotomy between their research and local life, effectively integrating into the local society. There are many examples of such scholars, such as Gu Jiegang, Xu Zhongshu, who had never been to or studied Sichuan before the War of Resistance Against Japan but later conducted relevant research and compiled their findings. Not to mention those who study tangible and audible cultural forms, such as architecture, historical geography, archaeology, and dialects, such as Liang Sicheng, Liu Zhiping, Dong Tonghe, who help local people understand their own cultural heritage while ensuring the relevance and progress of their own research.

Researchers studying their own locality have obvious advantages. However, as is widely known, being too close to the subject can also have drawbacks. However well-trained scholars who have long-term experience in living in a heterogeneous culture, looking back at the place where they once are nothing at all like the people who spend all their lives trapped in a cage they had fashioned for themselves. Accomplished researchers in this regard include Fei Xiaotong, Francis L. K. Hsu 许烺光, Lin Yaohua, and Martin C. Yang/Yang Maochun, while current examples include Han Min 韩敏 , a scholar of Chinese ancestry now living in Japan, who wrote 《回应革命与改革:皖北李村的社会变迁与延续》 [“Responding to Revolution and Reform: Social Changes and Continuity in Lici Village, North Anhui,”] and Ba Zhanlong, who wrote 巴战龙《学校教育·地方知识·现代性:一项家乡人类学研究》(此书为少数族裔用汉语乃至外国视角对自己本民族的回望与观察)[ “School Education, Local Knowledge, Modernity: A Study in Local Anthropology”] (this book represents a minority ethnic perspective, even a foreign perspective, on the introspection and observation of one’s own ethnicity).

Apart from Fei Xiaotong, the other three renowned anthropologists, especially Edmund R. Leach, known for his research on the social structure of the Kachin people in Myanmar, criticized the other three for their preconceived notions and tendency to distort information based on personal experiences rather than public experiences. Therefore, Han Min stated that in her research on hometown anthropology, she utilized her experiences of living and studying abroad, read ethnographies written by foreign scholars on Chinese ethnic groups, and collaborated with foreign scholars to enhance her insight into things that are often overlooked. She aimed to increase objectivity and address the issues of bias and self-isolation in hometown anthropology (see Han Min’s article 韩敏《一个家乡人类学者的实践与思考》一文,阮云星、韩敏主编《政治人类学:亚洲田野与书写》pp.260-261,浙江大学出版社2011年版)[“Reflections and Practices of a Hometown Anthropologist” in Ruan Yunxing and Han Min, eds., “Political Anthropology: Asian Fieldwork and Writing,” pp. 260-261, Zhejiang University Press, 2011)].

Anthropology originated as a top-down observation and examination of what is considered a disadvantaged civilization by self-proclaimed superior civilizations, with the hope of gaining deeper insights into the local culture. This type of observation has been regarded by nationalists and in nationalist discourse as a colonial perspective. I acknowledge the reasonable aspect of this view; it cannot be ignored. However, local hostility toward foreign researchers often keeps biases hidden and makes them difficult to identify and rectify, let alone absorb and change. In today’s anthropology, many studies are no longer focused on exotic cultures but rather on the introspection and reflection of intellectual elites on their own culture. This hometown anthropology, as characterized by Japanese anthropologist Suenari Michio, is a prominent characteristic of Chinese anthropological research.

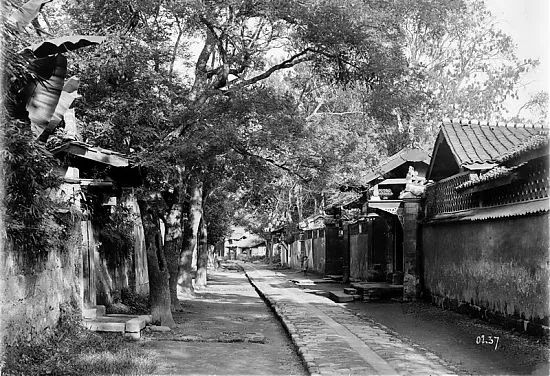

Wang Di’s work, while focused on historical research, also includes considerable investigative work and interviews to make up for the scarcity of documentary evidence. This is evident in his three books: “Street Culture,” “Teahouse,” and “Robe Brothers.” In “Street Culture,” he discussed his research methodology in hometown anthropology: “The academic exploration of Chinese street culture requires the application of interdisciplinary methods, especially those from history and anthropology. Chinese culture values inheritance, and many details of history and culture are passed down orally from one generation to the next. As a result, I was able to collect a significant amount of oral historical materials through interviews. From the establishment of New China until the reform and opening up, although Chengdu’s urban life and city have undergone dramatic changes, I was still able to collect past events through conversations with the elderly in teahouses, and explore the traces left by time in secluded alleys” (p. 14).

This approach aligns with Wang Di’s early intention, which resonates with Fernand Brodel’s view: “Small streets and alleys can take us back to the past… Even in today’s highly developed economy, those remnants of material civilization still speak of the past. However, they are vanishing before our eyes, albeit very slowly, and they will never be the same again” (p. 2). Unfortunately, many things in China, including Chengdu, that hold memories have changed or vanished without a trace.

In both “Teahouse” and “Street Culture,” Wang Di acknowledges and expresses gratitude to two “old tea customers,” Xiong Zhuoyun and Jiang Mengbi, for accepting his interviews multiple times, sharing their firsthand experiences in teahouses, and helping him connect with elderly people in Chengdu for interviews. For example, on June 21, 1997, the interview conducted together with Jiang Mengbi at Yuelai Teahouse might be one of the individuals they introduced.

Why do people enjoy frequenting teahouses? If we don’t interview the elderly who have experienced it firsthand, but merely rely on written records, the persuasiveness would be lacking, and it would seem to lack the flavor of life as well. The main reason people enjoyed going to teahouses was their preference for drinking tea brewed with fresh boiled water. At that time, fuel was expensive, and water had to be carried by porters from the river. There were no insulation facilities like today. Furthermore, selling hot water, brewing medicine, and cooking meat became profitable activities in teahouses, which also reduced the cost of fuel and carrying water for households (“Street Culture,” pp. 69-70).

You might think that going to teahouses was purely for enjoyment, but it was actually constrained by economic factors. Even the poorest people could afford a bowl of “overtime tea” in teahouses, as depicted in the illustration on page 90 of “Teahouse.” It’s similar to the first two lines of Su Shi/Su Dongpo‘s poem “He Ziyou Can Shi”《和子由蚕市》: “People of Shu although often poorly clothed and fed; forget all that in the joys of Spring Festival.” The entertainment in agrarian society had a dual nature of “pleasure mixed with pain” 痛快, although most of the time, the pleasure outweighed the pain.

In Chapter 3 of Paoge: Violence and Order in the Countryside of Western Sichuan in the 1940s , footnote 5, Wang Di interviewed Zhou Shaoji, a 75-year-old man at Yuelai Teahouse, in order to corroborate the reason why Li Jieren 李劼人 referred to the barber as “Dai Zhao” in the novel “Big Wave” 《大波》 and why barbers were not allowed to join the Robe Brothers. Oral and literary (even from works of fiction) evidence makes history more vivid and evidence more abundant. The same footnote also appears on page 346 of “Street Culture,” indicating that to understand Wang Di’s meticulous research on Chengdu, one needs to cross-reference his various books, which will reveal their ability and intention to use the same materials with different focuses. In the upcoming second part of the book “Teahouse,” which covers tea houses from 1950 to 2000, owing to the scarcity of archives and documents, interviews and oral histories gathered by Wang Di may become the primary historical materials and so surpass his earlier books.

In his preface to the Chinese edition of “Teahouse,” Wang Di wrote a paragraph that can be considered the key to understanding many of his works: “Western historians like to ‘change the scene after firing a shot,’ but I consider myself more like an anthropologist, conducting persistent long-term field research on a specific region. Writing ‘Breaking Out of the Closed World‘ gave me a macro understanding of Sichuan’s society and culture, but ‘Street Culture‘ and this book focus on Chengdu, and the microcosm of this city fascinates me. I am currently writing about teahouses and public life during the socialist era, also centered around Chengdu. These three books can be considered a ‘trilogy’ of the microhistory of a Chinese city and a narrative of Chengdu” (p. 2).

When studying a place that one is familiar with or even fond of, one is unavoidably influenced by emotions; some may be filled with nostalgia. However, Wang Di’s research effectively avoids this. Some people mistakenly believe that Wang Di romanticizes the past, but he directly addresses this in the preface to the Chinese edition of “Street Culture.” In fact, he does not shy away from the problems that existed in Chengdu in the past and present. However, he approaches them with relative academic objectivity. He is not simply writing down his personal opinions or creating romantic period dramas.

In response to the excessively nationalist attitude of some people towards Chinese culture and particular to the fascination of American sinologists, themselves profoundly immersed in modern Western society, with China’s past, Wang Di has a calm and moderate response: “They discovered that the simple relationships and the harmonious and stable situation of social community maintained by rituals in traditional Chinese society are highly valuable in today’s society. However, when they praise and appreciate the beauty of traditional Chinese society, they often overlook the negative factors that hinder social progress and development within it. Therefore, how to perceive the contradictions between tradition and modernity, backwardness and progress, inheritance and abandonment, which exist in a series of popular cultural studies, is still a question worthy of serious consideration” (“Entering,” p. 130). This is precisely the broader anthropological perspective of homeland that distinguishes Wang Di from traditional local cultural researchers at a deeper level.

II. New Exploration and Reassessment of Historical Materials

In general, every city has its researchers, but most are writing about and analyzing their own culture, and their limitations are evident. In other words, the perspectives and viewpoints of researchers from different regions studying a particular city are certainly to be appreciated. From this perspective, coastal cities, especially Beijing and Shanghai, have many researchers, some of whom are mentioned in Wang Di’s books.

In particular, foreign researchers in Shanghai, such as He Xiao 贺萧(Gail B. Hershatter) , Pei Yili 裴宜理(Elizabeth J. Perry , Ge Deman 顾德曼(Bryna Goodman) ,羅茲‧墨菲著(Murphey Rhoads), Wei Feide 魏斐德(Frederic Evans Wakeman, Jr). , and Han Qilan 韩起澜 Emily Honig , as well as scholars of Chinese ancestry such as Li Oufan 李欧梵 (Leo Ou-fan Lee) , Ye Kaidi 叶凯蒂(Catherine Yeh) , and Lu Hanchao 卢汉超 (Hanchao Lu), are a strong group. In comparison, when it comes to foreign researchers focusing on the development of modern and contemporary Chengdu, forgive my limited knowledge, but I have only heard of Shi Kunlun 司昆仑 (Kristin Stapleton) . Apart from Wang Di, it seems that there are no others who have returned after studying abroad to research the Chengdu they are familiar with.

The most direct answer to this situation is that it indicates Chengdu itself lacks sufficient appeal to scholars and is not a top-tier topic. However, the problem may be more complex than this answer. As an inland city, Chengdu’s openness in various aspects came much later than coastal cities, which is particularly disadvantageous for studying its modern urban development process.

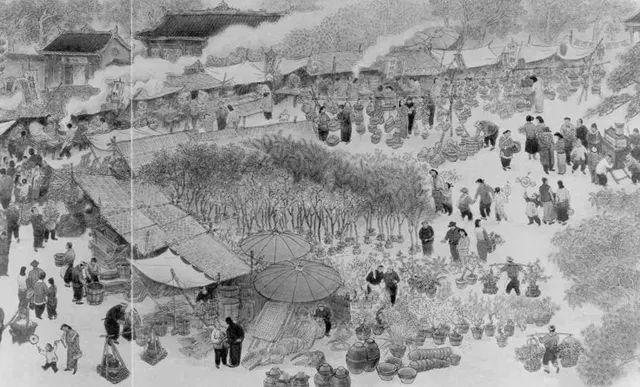

Wang Di shares the story of anthropologist David Crockett Graham in his books “Street Culture” and “Entering.” Many people, reading that story, are amazed at the protection of intellectual property rights in the United States. This amazement is reasonable, but if we stop there, we won’t understand the difficulties behind Wang Di’s writing in this section. We also fail to see one of the reasons why research on the modernization of Chengdu is weak, which is the lack of data, especially scarce photographs, compared to other cities. In order to compensate for this deficiency, Wang Di even includes the contemporary panoramic painting “Old Chengdu,” created by a modern artist, in his books “Street Culture” and “Tea House,” to provide readers with a more intuitive experience.

Part of painting “Old Chengdu”

- Images, especially photographs

From Wang Di’s textual explanations and narrative style, especially in his book “Entering,” we can see the evolution in his academic research. However, there is another transformation that he even forgets to mention, which is the shift from the abundant tables and illustrations (mainly maps) in “Breaking Out” – “the original book had 250 statistical tables, 32 maps and other illustrations, and the new edition retains 186 statistical tables and 12 figures” (Preface to the third edition of “Breaking Out”) – compared with his other books. Apart from the practical needs such as the actual operation of teahouses and surveys of hired workers, there are 24 tables and a large number of images and a few illustrations (fewer maps), forming a distinct contrast.

Tables are essential in quantitative historical research, relied upon by the positivistic approach of seeking evidence to determine fact, particularly favored in macro-regional studies and long-term comprehensive history. Compared to images, especially photographs, which are more sensory and intuitive, they have the ability to narrate details that go hand in hand with text. This is the result of the shake-up of historical methods and concepts behind the visual transformation in Wang Di’s books.

In the selection and use of images, there are noteworthy aspects in Wang Di’s books. Images are a part of history. No one disputes that. However, just how to use images to achieve research and interpretation of history is a profound question. Design historian Zhang Li once said, “There is no doubt about the historical significance of images for the study of visual culture and material culture. However, how to reconstruct dynamic and complex social networks, aesthetic models, ideologies 意識形態 and ideological blueprints from known image texts is a challenge that every historian who takes visuality as a starting point cannot avoid.” 《民国设计文化小史:日常生活与民族主义》p.38,江苏凤凰美术出版社2016年版) [“A Brief History of Design Culture in the Republic of China: Everyday Life and Nationalism,” p.38, Jiangsu Phoenix Art Publishing House, 2016 edition]. The works of Peter Burke‘s “Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence” and Craig Clunas‘ “Pictures and Visuality in Early Modern China” clearly demonstrate the historical value of images. Moreover, China has a tradition of combining images and historical records; sometimes a single image is more persuasive than many words.

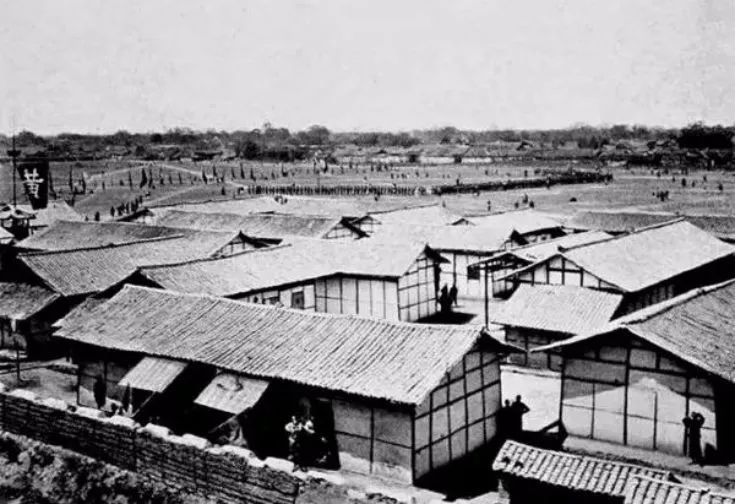

The illustrations in these six books by Wang Di can be divided into photographs (including ones he took, self-portraits, and reprints), maps (including hand-drawn maps), illustrations taken from old books and magazines, and contemporary paintings. This can be considered a comprehensive search for visual imagery related to Chengdu. However, there are still relatively few actual photographs, and all of them date back to the 20th century. There isn’t a single photograph from the 19th century, even though the research period for the book “Street Culture” is from 1870 to 1930.

Generally speaking, early photographs of a city are mostly related to foreigners and foreigners’ activities. This is determined by the invention, production, purchase, use, and dissemination of cameras. Foreigners who came to China to use cameras for photography were mostly teachers, explorers, diplomats, and missionaries, with the largest group being missionaries. The majority of the photographs, especially the photographs in Wang Di’s books, were provided by these individuals.

In Terry Bennett’s three-volume work “History of Photography in China,” there are mentions of missionaries, but there is no specific discussion of the relationship between missionaries and photography. There is only a small section in Chapter 2 of Volume 2, titled “Photographic Activities in Beijing,” which mentions medical missionary De Zhen 德贞 John Dudgeon . Gao Xi 高晞 in A Biography of Dudgeon: A British Medical Missionary and the Medical Modernization of the Late Qing Dynasty《德贞传:一个英国传教士与晚清医学进代化》 focuses on writing a biography and naturally does not mention the importance of John Dudgeon’s “Tuoying Qiguan” 《脱影奇观》[bilibili video 脱影奇观] [The Wonders of Getting an Exact Image of Things] to the history of Chinese photography. Gao Xi, in his chronicle of John Dudgeon’s life, clearly states that in 1855, at the age of 18, Dezhen wrote a book in English called “Extraordinary Wonders Beyond Shadows,” which was later translated into Chinese in 1873 and became an important document in the history of Chinese photography. In Ma Yunzeng’s 马运增等著《中国摄影史(1840—1937)》 “History of Photography in China (1840-1937)” (China Photography Publishing House, 1987 edition), John Dudgeon is only referred to as a doctor, with no mention of his identity as a medical missionary, let alone his lifelong efforts to end the opium trade.

In recent years, Chen Shen and Xu Xichen’s 《中国摄影艺术史》”History of Chinese Photography Art” (Sanlian Bookstore, 2011 edition) briefly mentions him in a few parts of their book, such as “Cultural Missionary,” “The ‘Tuoying Qiguan’ and Editor De Zhen,” and “Ding Weiliang’s Translation of ‘Gewu Ru Men’.” However, overall, we still lack an account of the relationship between missionaries and the modernization of Chinese cities, particularly in terms of visual representation. Even prominent scholars who have made outstanding contributions to the study of art and photography in China, like Wu Hong in his book《聚焦:摄影在中国》 “Zooming In: Photography in China,” seem to have overlooked this.

Neglect of this issue resulted in significant shortcomings in historical materials, including images, for the study of China’s modernization, especially urban modernization. In the past, when people studied missionaries, they mostly focused on religious and cultural conflicts, charity work, social relief, and medical education. However, the history of photography in China is incomplete without the photographs taken by missionaries and the historical materials they contributed. Unfortunately, many people are not aware of this issue, but after reading these six books by Wang Di, I feel that this is an important problem.

Among Wang Di’s six Chinese books, “Street Culture,” “Teahouse,” and “Vanished” are the ones with the most photographs, especially “Street” with 118 images (including maps), “Teahouse” with 95 images (including maps), and “Vanished” with 183 images (plus a separate map). I didn’t include the illustrations from old books, maps, and contemporary paintings in the statistics. Therefore, the number of photographs in these three books would be 36, 47, and 100, respectively.

Why are there only three photographs taken by missionaries in the book “Teahouse”? In fact, the main photographers for the book “Teahouse” were Chen Jin and the author himself, both of whom are contemporary photographers. The only photograph of the teahouse taken before 1949 was taken by missionary B. Brockmann (p.160), and its preciousness is self-evident. This may further contribute to the similarity in photographs between the first and second parts of “Teahouse,” and it can be expected that the first part will have relatively fewer interviews.

Street Culture’ and Vanished delve more into the various aspects of daily life, so there are more photographs taken by missionaries. Missionaries are less concerned with teahouses than with disadvantaged groups such as beggars and abandoned infants, which allows them to approach social gospel issues. They also focus on temples, fortune-telling, and other topics because the gospel needs to address these belief-related issues. Moreover, these photographs were taken at an earlier time.

In summary, the early photographs of Chengdu included in these books were mostly taken by missionaries, as well as foreign teachers, diplomats, and geographers. A similar situation probably occurred during the early modernization process in coastal areas. This is a cultural phenomenon worth noting from the perspectives of visual history, photography history, and Sino-foreign visual communication.

At the same time, regarding the images in these books, they also include the reproductions provided by William G. Sewell, an educational missionary, in his book 《龙骨(一个外国人眼中的老成都》 “Dragon Bones: A Foreigner’s Perspective of ‘Old Chengdu’,” which contains the paintings of Yu Zidan. [Translator’s Note: William G. Sewell has at least two books still in print: I Stayed in China (1966) and The People of Wheelbarrow Lane (1970).End Note] There are also several photographs reproduced by Wang Di from David Crockett Graham‘s book, for which he made great efforts to obtain authorization to reproduce. David Crockett Graham was also a typical scholar-missionary.

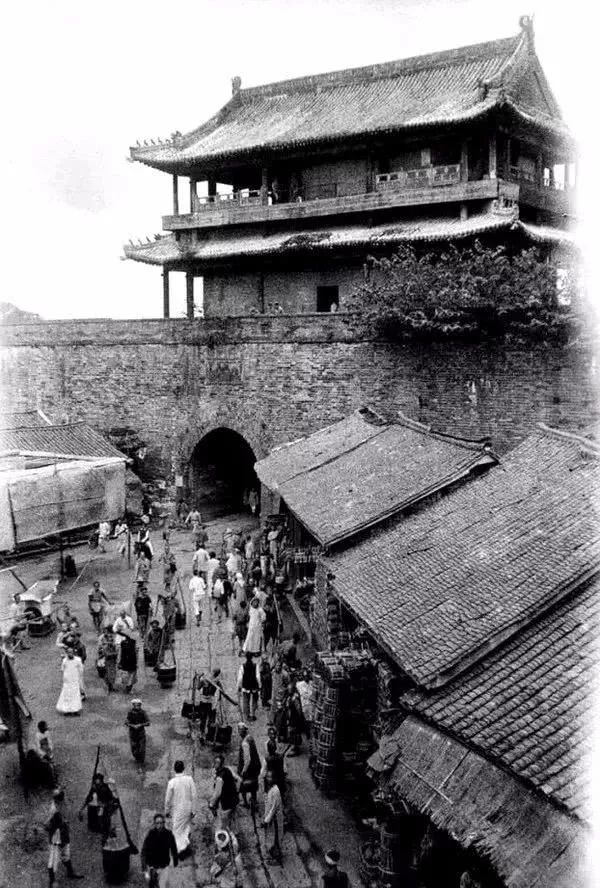

Regarding the Chengdu city wall, apart from the writings of geologist Hubbard, there is a historical account of the Chengdu city wall by missionary 陶然士(Thomas Torrance 1871—1959) published in the 1916 issue of “Huaxi Church News,” No. 10 (footnote in “Street Culture,” p. 36). [Translator: see also Sichuan Daily article on Torrance.] In addition to a photograph of foreign teachers gazing into the distance from the city wall, there is a photograph by missionary Edward Wilson Wallace 吴濬明(吴哲夫) (Wu Zefu also known as Wu Junming). In fact, there are more exquisite and clear photographs of the Chengdu city wall in the possession of the descendants of Canadian missionaries, which are currently being exhibited and stored in Xinchang Town, Dayi County. The combination of text and images is highly informative.

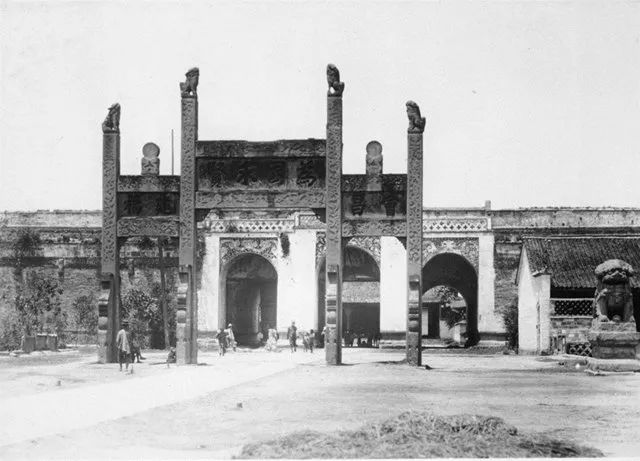

There are many similarities in the use of images in Wang Di’s books, mainly because they are closely related to the topics discussed and are all related to the same city. The scarcity of photographs is the main reason for this. I remember that in one of the books, Wang Di mentioned that Si Kunlun 司昆仑 (Kristin Stapleton) provided him with information from Toronto, and from that direction, he sought out a lot of information about modern Chengdu society, especially photographs. This is because many missionaries in the Chengdu area were sent from Canada (which was still part of Britain at that time), so they could obtain richer visual information about Chengdu. In 2012, Sichuan Literature and Art Publishing House published a thick album titled 《成都 我的家》 “Chengdu, My Home,” compiled by the Canadian Old Photos Project Group, which contains a rich collection of photographs depicting various aspects of Chengdu’s everyday life. Some of these photographs had never been seen before, such as the tall archways on East and West Yujie Streets.

[Interlude: photo from 《成都 我的家》 “Chengdu, My Home,”

See also the translation on this blog of 加拿大差会在华西地区的社会文化活动*as 2013: Canadian Missionaries in West China: Enriching Sources for Local History Research

———以华英书局传教士为中心的讨论

Translated from article about Chengdu, My Home – The Story behind “Chengdu Old Photos from Canada” Art Exchange VOL.02/2012 | Zhang Yameng

Photo: Huaxi Union University organizes students to participate in the activities of the China Christian Youth Association’s Rural Service Team.

These were the lives and stories of three generations of Canadians in Chengdu. Over 100 years ago, a group of Canadian friends came to Southwest China, spreading Western medicine, establishing medical schools, learning Chinese, and promoting social change. While spreading science and medicine to China for decades, they also left behind countless precious photographic images, providing valuable historical records and treasures of that time. These Canadian volunteers, in the prime of their lives, came to settle in Sichuan with the ideal of achieving something meaningful and gave themselves Chinese names, as well as their descendants born in Sichuan. Here, they established the first Western medicine clinic in western China (now the Second People’s Hospital of Chengdu), bringing Western medicine to the people of Sichuan. They founded the West China Union University, with a focus on medicine and dentistry and a balanced emphasis on humanities and sciences (now the West China School of Medicine at Sichuan University), making it the birthplace of modern dental medicine in China. Through their educational and medical endeavors, they spread aspects of Western modern culture, education, medical knowledge, and promoted social progress. They campaigned for social reforms and called for change, contributing to the development of modern civilization. Amidst their busy work, they used cameras to document China, Sichuan, and Chengdu at that time.

End interlude]

Furthermore, the reason why “Vanished” has the most photographs, especially rare ones, among Wang Di’s published books is not only due to the need for dissemination as a popular book but also because of two sources that significantly increased the number of previously unseen related photographs. The first source is from the missionary and sociologist 甘博 (Sidney David Gamble,1890年7月12日—1968年3月29日), and the second is from the renowned photographer Carl Mydans of the American magazine “Life.” The photographs from both sources are now publicly available on the internet and have no usage restrictions [Translator note: copyright by Time Inc. for non-commercial use only. See 5000+ photo collection by Mydans online].

Sidney David Gamble traveled to seventeen provinces and cities in China, taking thousands of photographs, which have been compiled into fifteen volumes in the 《甘博摄影集》 “Gan Bo Photography Collection.” During his travels in Sichuan, including Chengdu, Gamble collaborated with rural education expert Fu Baochen, and his works include five collections of surveys, including “Social Surveys in Beijing.” Carl Mydans , on behalf of “Life” magazine, came to China in 1941 to photograph and conduct interviews for several months. One of his works was the eight-page special feature on Longquanyi 龙泉驿 entitled “A Small Town That Makes China Invincible,” published on November 24, 1941. According to Hu Kaiquan’s article in the Longquanyi Archives, “A Contemporary Interpretation of the ‘Longquanyi Special Feature’ in the 1941 American ‘Life’ Magazine” (Journal of Literature and History, 2017, Issue 2), the completion of this special feature was the result of official introduction, family support, and the assistance of Christians.

In addition to discussing the collection of photographs, I will briefly mention some issues of historical material omission. As I mentioned earlier, Wang Di had a strong desire to exhaust all available historical materials, but actually achieving that is no easy task. For example, while writing the books “Street Culture” and “Teahouse,” Wang Di made use of many personal records but overlooked the following valuable historical sources.

For example, Wang Kaiyun‘s “Xiangqi Tower Diary” 王闿运《湘绮楼日记》. During his eight-year tenure as the abbot of Zunjing Academy, there are some historical materials related to the Sichuan-Chongqing region and Chengdu available. The travel diary Walking Along Cliff Boardwalks Through Gorges and In the Rain with Draft Poems 《栈云峡雨》 by Japanese scholar Takezoe Shinichiro 竹添进一朗 recorded his observations on a journey from Beijing to Chengdu in 1876, including book purchases, tea drinking, social gatherings, and descriptions of the streets, all worth noting. From 1901 to 1920, the renowned Japanese architect Itō Chūta 伊东忠太 conducted six on-site architectural surveys in China, including an eight-day stay in Chengdu in 1902. His descriptions of Chengdu’s architectural forms, streets, and even toilets are valuable historical materials.

Although historical materials are difficult to gather, it is always good to gather them from diverse sources.

- Bamboo branch songs and folk literature

Wang Di believes that when studying local history, there are generally four types of available materials that can be utilized:

- Official texts,

- Mass media,

- Surveys and statistics, and

- Personal records

(“Street Culture,” p. 8). Regarding this, the translator of the book “Street Culture,” Li Deying, adds: “This judgment roughly includes important materials in the study of local history, but the author believes that folk contracts and materials (such as account books, genealogies, inscriptions, folk songs, legends, etc.) are also very important materials” (Edited by Pei Yili et al., “What Is the Best Historiography,” p. 33 裴宜理等主编《什么是最好的历史学》, Zhejiang University Press, 2015).

I don’t think Wang Di would oppose this addition by Li Deying because folk stories, although often legendary, serve as good materials for understanding social attitudes, customs, and daily life. The writing of bamboo branch songs 竹枝词 is closely related to the popular sentiments, customs, and daily life of that time, and it has its own significant historical value. Otherwise, Wang Di would not have consciously used them in his works. However, he did not express it as explicitly as Li Deying did when categorizing and comparing.

How does this historical value come about? Because the truth in literature and the concrete occurrence of a certain event are different. The truth in literature has a certain probability, and it does not necessarily mean that something definitely happened. However, from the perspective of the history of mentality, social sentiments, and the internal logic of people’s lives, it reflects the thoughts and emotional changes of that era in a genuine way.

In “Teahouse” and “Street Culture,” the quoted novels involve authors like Li Jieren, Ba Jin, and Sha Ting, who all reflect the thinking and social attitudes of that time. Although they are presented through the inner logic of characters’ actions and their development, for example, in the book “Street Culture,” Li Jieren’s novel is used to demonstrate how Li Zheng and Jie Zheng organized the people’s self-defense during social unrest. Even though there may be no corresponding recorded historical material in local history, its authenticity should not be denied.

Of course, this raises the question of how to handle the historical matters and social judgments contained in literary works. Although bamboo branch songs belong not just to Sichuan or Chengdu, it is rare to see someone like Wang Di interpreting them from a sociological and historical perspective. Here he departs from traditional Chinese methods for understanding history. If taken far enough, the “Book of Songs” “Shijing” is not simply a work of literature for literature’s sake. This permits interpretations like the “Book of Songs Scene” by Liu Shahe.

Similarly, the authenticity of literary descriptions in “Records of the Grand Historian,” such as the “Feast at Swan Goose Gate (鸿门宴)” in the “Biography of Xiang Yu,” has always been considered to be excessively detailed to the point that some people believe Sima Qian must have completely fabricated it because he was not an eyewitness. However, in depicting the personalities of Xiang Yu and Liu Bang, it was certainly very useful. The victory or defeat of an individual is the result of a combination of various factors, including timing and circumstances, but sometimes it is also determined by unknown details and personalities. This is something that those who cannot appreciate the contingency of history—of course, the ultimate direction of human history is another matter—cannot understand its charm.

Wang Di’s friend, 司昆仑 [Kristin Stapleton], who also excels in researching Chengdu, provided Wang Di with microfilm copies of “Popular Daily” 《通俗日报》and “National Public Bulletin”《国民公报》 which facilitated his research (“Street Culture,” p.26). In fact, the benefit he gained from this aspect added to the uniqueness of his books “Street Culture,” “Teahouse,” and “Vanished.” However, the use of bamboo branch songs and folk stories has given Wang Di’s research something earlier Chengdu studies did not have, and that is what makes his books “Street Culture,” “Teahouse,” and “Vanishedance” special.

Although Wang Di’s use of Chengdu’s bamboo branch songs is far from being as delicate and exhaustive as it could be, since he used Lin Kongyi’s book 孔翼《成都竹枝词》 [“Chengdu Bamboo Branch Songs]” instead of 杨尚孔主编的《竹枝成都:本土文化的经典记忆》[ “Bamboo Branch Chengdu: Classic Memories of Local Culture,] edited by Feng Guanghong and Yang Shangkong, which contains 2,071 bamboo branch songs about Chengdu. Even so, his use of non-historical materials has brought enlightenment to Chengdu researchers.

This prompts us to revisit the beginning and ending of Wang Di’s “Teahouse.” Traditional Chinese academic writing might consider them redundant. However, the merit of this approach of looking again is that it enables us to examine to what extent an individual’s resilience and adaptability in the face of drastic institutional changes and social transformations. Specifically, to what extent can habits withstand external pressures, whether they are shaped by the system (economic, political) or propaganda (ideological indoctrination, advocating new lifestyles), and how do they affect what changes and what does not through time and space. This approach enables us to understand that the interplay between the state and the locality, the elite and the grassroots, and the radical changes in society and customs is far more complex than we had imagined. Thus, as we consider diverse issues, we should avoid a convenient binary judgment that only considers one side or the other.

3. Using “Huaxi Church News” 《华西教会新闻》as a Source

I would like to emphasize a viewpoint that when studying the process of modernization in Chinese cities, it is evident that neglecting the role of missionaries in this process leads to significant shortcomings. The contributions of missionaries cannot be ignored when examining various aspects of China’s modernization process, including urban development, healthcare, education, culture, charity, social organizations, and moral reconstruction.

Given the continuous coverage and documentation of Sichuan (including Chongqing), Tibet, Guizhou, and Yunnan provinces for 45 years (1899-1943) by “Huaxi Church News,” 《华西教会新闻》conducting a thorough study of this publication is crucial for understanding the modern history of these regions. In comparison, there may be fewer researchers focusing on “Chongshi Bao” 《崇实报》published in both Chinese and French by the Catholic Diocese of Eastern Sichuan in 1904. Although there are still many aspects of “Huaxi Church News” that require further exploration, scholars have made some progress in its discovery and research since the beginning of the previous century, particularly in the early years of this century.

On advances in research prior to 2009, 张伊、周蜀蓉《<华西教会新闻>研究综述》(《宗教学研究》2009年第一期)[Zhang Yi and Zhou Shurong’s “Review of Research on ‘Huaxi Church News’'” (Religious Studies, 1/2009)] provides a relatively clear overview.

For the achievements since then, based on the papers I have seen, noteworthy are:

- Bai Xiaoyun’s “An Investigation of Missionaries on Religion and Folk Beliefs in Southwest China: With a Focus on ‘Huaxi Church News'” (Religious Studies, 2012, Issue 2),

- Bai Xiaoyun and Chen Jianming’s “Evolution of the Publication Purpose of ‘Huaxi Church News’ and the Localization of Christianity in Sichuan” (World Religious Research, 2013, Issue 3),

- Hui Fengping’s “Multidimensional Presentation of ‘Huaxi Church News’ in Late Qing Chongqing” (Master’s thesis, Southwest University of Political Science and Law, 2018),

- Zhang Baobao’s “Protestant Missionaries in Late Qing and Early Republican Era and Sichuan Society: With a Focus on ‘Huaxi Church News'” (Master’s thesis, Shanghai Normal University, 2018), and

- Zhu Yaling’s “A Study of the Eastern Tibetan Region as Portrayed by Western Missionaries: Focusing on ‘Huaxi Church News’ (1899-1943) and Its Accounts of Tibet” (Doctoral dissertation, Sichuan University, 2018)

Among the published works, Chen Jianming’s 陈建明的《近代基督教在华西地区文字事工研究》[“Research on Modern Christianity’s Literacy Ministry in Western China” (Bashu Publishing House, 2013 edition)] extensively explores “Huaxi Church News.”

Overall, an increasing number of researchers have been studying “Huaxi Church News” since 2013, mainly due to the relative ease of accessing the materials. In 2013, the National Library Press published a reprint edition of 32 volumes of “Huaxi Church News,” which has greatly facilitated research in the fields of journalism, regional studies, and religion.

Since many people have utilized and mentioned “Huaxi Church News,” what makes Wang Di’s use of this material special? Wang Di’s attention to “Huaxi Church News” should be traced back to the 1980s when he studied under Wei Yingtao, who can be considered a pioneer in using “Huaxi Church News” to study the modern history of Sichuan, particularly the Railway Protection Movement, after 1949. Such collection and analysis of data, as well as academic perspectives, undoubtedly influenced Wang Di’s attention to this publication.

In fact, Wang Di in his book “Breaking Out of the Closed World: A Study of the Upper Yangtze River Region Society (1644-1911)” (Breaking Out), when discussing the Railway Protection Movement, Wang Di cited a remarkable fact about the mobilization of local elites, which would be difficult to know from other sources besides “Huaxi Church News.” He states, “According to ‘Huaxi Church News,’ in Deyang, ‘representatives from Chengdu came to this county and brought a long list of people who joined the Railroad Protection Comrades’ Association, among whom almost every person of some status joined the association'” (“Breaking Out,” p. 301). This information is quite helpful for analyzing the social trends and political maneuvering of that time.

In the English edition preface of Street Culture: Chengdu’s Public Space, Lower-Class People, and Local Politics (1870-1930), Wang Di specifically mentioned the assistance he received from Si Kunlun in terms of collecting rolls of films containing parts of “Tongsu Ribao” (Popular Daily) and “Guomin Gongbao” (National Bulletin) for his use (“Street Culture Culture,” p. 26). One of the translators of the book, Li Deying, stated in the “Afterword,” “Wang Di put a great deal of effort into collecting materials. The main sources he used, including ‘Guomin Gongbao,’ ‘Tongsu Ribao,‘ ‘Tongsu Huabao,‘ and ‘Huaxi Church News,’ are important newspaper materials for studying the social, economic, and cultural aspects of this period, but these materials have rarely been used by previous scholars” (“Street Culture,” p. 402).

When Li Deying made this statement in 2005, “Huaxi Church News” was indeed rarely used. Therefore, when “Street Culture” extensively quoted “Huaxi Church News” in seventy-three instances (as mentioned by Zhang Yi and Zhou Shurong), it naturally drew people’s attention. Because “Street Culture” discusses social reforms, changes in political power, urban space competition, and other topics, which are extensively covered in “Huaxi Church News,” the frequency of references is relatively high. In the book “Vanished” (“The Vanished Ancient City: Memories of Daily Life in Late Qing and Early Republican Chengdu” ), which is a popular edition of “Street Culture” and “Teahouse” (“Teahouses: Public Life and Microcosm in Chengdu, 1900-1950”), the frequency of references to “Huaxi Church News” is slightly lower, with “Tea Houses” having the least references. This frequency of use aligns perfectly with the photographs taken by missionaries that Wang Di discussed.

Aspects such as beggars, vagrants, urban sanitation, and street clean-up, as well as the reforms of “Jian, Chang, Chang, Xiang” (brothels, theaters, factories, singing houses), which Zhou Xiaohuai observed after his return from a visit to Japan, closely reflect the living environment of missionaries. Therefore, in “Huaxi Church News” references to these things often appear.

Historical accounts about beggars often appear in the “Huaxi Church News” – both missionaries He Zhongyi 何忠义 (George E. Hartwell)and Pei Huanzhang 裴焕章(Joshua Vale)wrote articles about beggars. These articles, along with occasional reports in the “National News” 《国民公报》and “Popular Pictorial” 《通俗画报》of that time, accompanied by photographs taken by missionaries, formed the overall picture of Wang Di’s research. Pei Huanzhang/Joshua Vale mentioned in the “Huaxi Church News” that religious books were distributed in villages, streets, and especially teahouses, indicating their awareness of the importance of teahouses in Sichuan, especially in Chengdu.

In fact, in the study of urban modernization, “Huaxi Church News” was extensively used in Wang Di’s works, as well as in the works of Kristin Stapleton, such as Civilizing Chengdu: Chinese Urban Reform, 1895-1937 and Fact in Fiction: 1920’s China and Ba Jin’s Family. Furthermore, subsequent works like Hui Fengping’s “The Multidimensional Presentation of ‘Huaxi Church News‘ on Late Qing Chongqing” (Master’s thesis, Southwest University of Political Science and Law, 2018) 惠凤萍《<华西教会新闻>对清末重庆的多维呈现》 and Zhang Baobao’s “Christian Missionaries and Sichuan Society in the Late Qing and Early Republican Period – Centered on ‘Huaxi Church News’” (Master’s thesis, Shanghai Normal University, 2018) 张宝宝《清末民初基督教新教传教士与四川社会——以<华西教会新闻>为中心》 also discussed the content related to the cities of Chengdu and Chongqing in the publication.

This shows that “Huaxi Church News” plays an irreplaceable role in explaining the modernization process of Chengdu and Chongqing. The use and handling of materials reflect changes in historical concepts and adjustments in research perspectives. Just as Si Kunlun 司昆仑 Kristin Stapleton often used official notes from the U.S. Consulate to the Chinese government mentioned in her book “Fact in Fiction: 1920’s China and Ba Jin’s Family,” which have been hardly noticed by domestic researchers – neither did Wang Di notice these sources. This illustrates the significant role of expanding materials in reconstructing history. In this sense, emphasizing that historiography is based on historical materials, as Fu Ssu-nien (Chinese: 傅斯年; pinyin: Fù Sīnián; 26 March 1896 – 20 December 1950) said, is not without reason.

III. Struggle between official and folk forces: memory in street names

Wang Di mentioned that “in the courtyard where I lived during my childhood, there were Buhou Street and Jiaoban Street in front” (Vanished, pp. 4-5), which is actually a mistake for Jueban Street. Ming Dynasty essayist Zhang Dai (張岱; pinyin: Zhāng Dài, courtesy name: Zongzi (宗子), pseudonym: Tao’an (陶庵)) (1597–1684) , in Volume III [sic] of 夜航船 “Night Boat,” in the chapter “Tuo Ya Diao” 《脱雅调》, discusses the naming of streets, such as “Niushi Lane being commonly referred to as ‘You Sini Lane'” which he calls “Tuo Ya Diao.”

[Translator’s Note: I didn’t find 《脱雅调》in Volume III in ctext.org; it turns out that it is in another book equally entitled 夜航船 “Night Boat,” by Zhang Qu’an same title: 庄蘧庵著《夜航船》卷三,正有《脱雅调》. I found a note about this problem online: “Night Voyage” mentioned by Qian Zhongshu about recording the “loss of elegance” 《脱雅调》is not the Ming Dynasty Zhang Dai’s “Night Voyage” mentioned in “Night Reading Collection”. It is well known that Zhang Dai had a “Night Voyage”, but few people know that Zhuang Qu’an in modern times also wrote a “Night Voyage”! In Volume Three of Zhuang Qu’an’s Night Voyage published by Guangyi Bookstore in 1920, there is indeed a chapter called “Loss of Elegance”! See the upload of Zhang Qu’an’s 1920 book “Night Voyage” to Wikimedia Commons by Fudan University. End note]

Qian Zhongshu criticized “Tuo Su Diao,” for completely reversing the importance of elegance and vulgarity (Qian Zhongshu’s Manuscript Collection: Rong’an Hall Notes, 201 cases, Commercial Press 2003 edition). Qian believed that the common pattern for street names is to prioritize vulgarity before elegance, and seeking elegance from vulgarity. He gave the example of changing “Stinking Vagina Lane” to “Shoubi Lane,” similar to changing “literary person” to “literary worker.” I admit that Qian’s statement is indeed more common and reasonable, but Jueban Street does resemble Zhang Dai’s description, as it should have been derived from the actual situation by literati, but ordinary people did not understand it, so they called it “Jiaoban Street.”

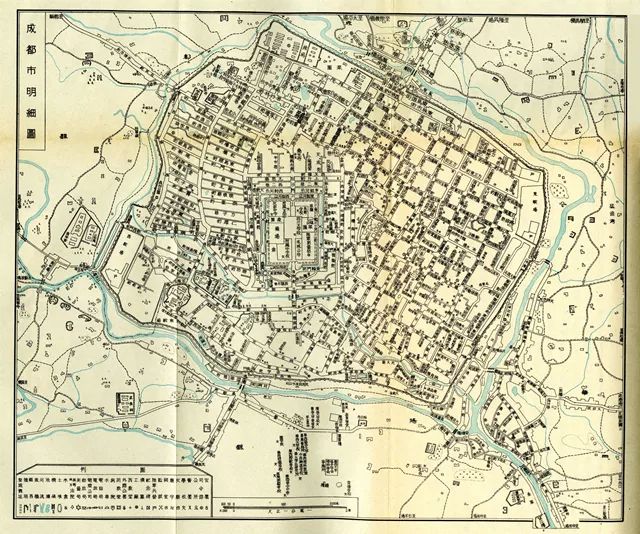

So how did Jueban Street 爵版街 actually get its name? In his book “Breaking Out,” Wang Di talks about the “administrative governance structure” of the Qing Dynasty and mentions the three branches of the civil government of the province: the Provincial Governor’s Office; Provincial Treasury Management; Provincial Governor’s Office Censorate/Accounting (p. 283). They were all connected to the Provincial Governor’s Office and became street names in Chengdu. The Governor’s Department Street is actually today’s Huaxing East Street, which was connected to the Treasury Street before the construction of Hongxing Road, and Jueban Street was connected to the Treasury Street as well.

This indicates that Wang Di was not unaware of the origin of Jueban Street, as its name came from the “perusal and verification of documents” process of the Censorate Hall. Officials’ identification verification, county records, and verification, as well as scholars’ social interactions, all required printing at this location. In a sense, this street became the “business card (plate) street” of the Qing Dynasty.

Why did such a street form? I have analyzed this in more detail in the preface of the new edition of my book [Translator’s Note: GT translate in URL of book page on a Taiwan bookstore website includes part of Chapter One. End Note] “Entering Chengdu from the sidelines of history: digging into a thousand years of history, recording a city, resurrecting generations of people” 从历史的偏旁进入成都:挖掘千年史,记录一座城,复活几代人 in the chapter “The Sociological Process of Urban Growth in a City” (China Development Press, 2015 edition), but I will briefly discuss it here. The surroundings of Jueban Street were filled with mutually dependent industries. Apart from the Provincial Governor’s Office mentioned earlier, there were also nearby streets such as Duyuan Street (Governor’s Mansion) and Tidu Street (Commander’s Office). At that time, transportation was inconvenient, and having government offices concentrated in one area made work simpler and less expensive. At the same time, streets like Kejia Lane, Shuyuan Street (gathering and lodging places for examination candidates), as well as Ziku (Xizigong Street), were located nearby, forming a street that provided commercial services to officials, scholars, merchants, and others for printing business cards. This should come as no surprise.

The formation of old streets, as well as their naming, is significantly different from the current emphasis on planned human intervention. The principles of street formation and naming were based on the characteristics of life itself. Streets existed in a mutually dependent state, forming different kinds of chains of industrial production. For example, near Cotton Street, there would be Hat Street, and next to Rice Market Street, there would be Mill Street.

In other words, to some extent, you can even deduce the nature of the next street and its name from a particular street. This is what I mean by spontaneous order growth in the sense of Hayek. Of course, this does not mean that the formation and naming of streets have no traces of human intervention.

Frankly speaking, for many street names like Yanshikou (Salt Market), Niushikou (Beef Market), and Cotton Street 盐市口、牛市口、棉花街, it is impossible to determine the specific individuals or organizations responsible for their naming. Similarly, just as marketplaces and markets formed spontaneously based on considerations of transportation, the naming and physical formation of streets followed a similar pattern.

I have not yet read Kristin Stapleton’s Civilizing Chengdu: Chinese Urban Reform, 1895-1937 , [Chinese language edition 司昆仑, 新政之后:警察、军阀与文明进程中的成都 (1895-1937). 四川文艺出版社, 2020] nor have I seen her article on Yang Sen’s “New Policy” in Chengdu. If she only discusses it from a progressive or elite perspective, she may overlook the perspective I am about to mention, which is also not extensively addressed in Wang Di’s book “Street Life.”

From Zhou Shanpei’s urban improvement initiatives to Yang Sen’s more forceful urban development and road construction, it was indeed a practice of controlling the distribution of benefits and using power to intervene in people’s lives. The spaciousness of the roads and the construction of multi-story buildings served as a showcase in material space, demonstrating their power.